Balancing Free Expression and Hate Speech in India

Legal Challenges in Defining the Limits of Speech

Abstract: This article examines the tension between India’s robust constitutional guarantee of free speech and its laws against hate speech. Article 19(1)(a) of India’s Constitution guarantees citizens the right to free expression, but Article 19(2) permits “reasonable restrictions” for security, public order, decency, etc. India has specific criminal provisions – notably IPC Sections 153A (promoting enmity), 295A (insulting religion), 505 (public mischief) – targeting speech that incites hatred or violence. Recent Supreme Court guidance, high court rulings, and data reveal a sharp rise in reported hate-speech incidents, prompting debate on where to draw the line. Internationally, the U.S. strongly protects hate speech (barring incitement), whereas the EU criminalises much hate speech. The article analyses recent Indian case law and data (NCRB crime statistics, NGO reports) to show how courts are navigating this balancing act and suggests that Indian law increasingly treats hate speech as a grave public-order harm requiring a firm legal response.

Constitutional Protections and Limits

The Indian Constitution enshrines freedom of speech and expression as a fundamental right. However, unlike the First Amendment in the U.S., Article 19(2) explicitly permits “reasonable restrictions” on speech in the interests of sovereignty, public order, decency, defamation, incitement, etc. This reflects India’s history and plural society: whereas the U.S. adopts an almost absolute free-speech approach (protected except for narrow categories like incitement or true threats), India’s constitution permits preventive restrictions to maintain harmony. The Supreme Court has interpreted these restrictions narrowly: e.g. in Kedar Nath Singh v. Bihar, the Court upheld sedition laws only to the extent that speech is intended or likely to cause public disorder or incite violence. Similarly, the Court has required a “proximate nexus” between speech and actual violence or disorder, effectively invoking standards akin to the U.S. Brandenburg “imminent lawless action” test for hate speech to be punishable. For example, in Patricia Mukhim v. State of Meghalaya (2021), a Facebook post criticising government inaction was held not to be hate speech because it lacked intent to promote ill-will. At the same time, courts recognise that hate speech need not produce immediate violence to be harmful; psychological harms and lasting social unrest can also justify restriction.

Statutory Prohibitions on Hate Speech

Indian law contains multiple provisions aimed at hateful or communal speech. Section 153A of the IPC criminalises “promoting enmity between different groups on grounds of religion, race, place of birth, residence, language, etc.”; Section 153B covers statements prejudicial to national integration; Section 295A punishes deliberate and malicious insults to a class’s religious beliefs; and Section 505 penalises any statement causing public alarm or inciting a class to commit an offence. These have long been used to prosecute communal rhetoric. (A new criminal code, the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita 2023, renumbers these offences but retains similar substance.) The PSA Legal Counsellor notes that, unlike the U.S., India explicitly empowers the government to punish insulting speech – e.g. 295A carries up to 3 years’ jail for insulting religious beliefs. Such laws reflect India’s aim of preventing mob violence: for instance, politician Kamlesh Tiwari was prosecuted under 295A and even held under preventive NSA after he insulted the Prophet, following violent protests. Unlike the U.S. (which lacks laws against mere offence), Indian law tolerates more restrictions to preserve harmony among its many communities. The European Union takes a similar stance: EU law requires member states to criminalise public incitement to violence or hatred on grounds of race, religion, or ethnicity.

Judicial Approach and Key Cases

Indian courts have repeatedly affirmed that mere speech – however offensive – cannot be criminalised unless it incites disorder. In the sedition case Kedar Nath Singh, the Supreme Court “read down” Section 124A, holding that only words with the intention or tendency to create public disorder are punishable. Following this logic, in Amish Devgan v. Union of India (2022), a nine-judge Bench took a stricter stance on hate speech. The Court quashed prosecutions lacking proximate violence, holding that mere insults or disparagements are not punishable absent a “clear and present danger” of disorder. However, Amish Devgan did reaffirm that hate speech – particularly if it vilifies or humbles a group and risks violence – is “hate speech which tends to vilify, humiliate and incite hatred or violence against the target group.”

More recently, the Supreme Court has been unequivocal that aggressive hate speech must be curbed. In Vishal Tiwari v. Union of India (May 2025), the Court (CJI Sanjiv Khanna and J. Sanjay Kumar) declared that “attempts to spread communal hatred and indulge in hate speech must be dealt with an iron hand,” because such speech “cannot be tolerated”. The Court noted that hate speech “leads to loss of dignity and self-worth of the targeted group… erodes tolerance and open-mindedness… Any attempt to cause alienation or humiliation of the targeted group is a criminal offence.” Although the Court did not issue new guidelines in that case, it expressly warned authorities to treat communal incitement vigorously, and recalled its April 2023 order directing all States to Suo motu register FIRs even without a complaint for hate speeches. Similarly, in April 2023, the Court (per Shaheen Abdullah v. UOI) instructed every state and union territory to immediately book hate speakers under Sections 153A, 505, 295A, etc., “even if no complaint has been made”. Refusal to act was threatened with contempt.

At the High Court level, recent judgments echo this stern tone. In February 2025, the Kerala High Court in PC George v. State of Kerala refused anticipatory bail to a legislator who had labelled all Muslims as “terrorists.” Justice Kunhikrishnan noted that existing punishments (fines or short jail terms) are insufficient, and recommended stricter hate speech laws, saying such statements “should be nipped in the bud.” The judge emphasised that seasoned politicians cannot escape consequences by token apologies, and that granting bail in such cases “would send the wrong message” about communal harmony.

These decisions illustrate the balancing act: the Indian judiciary recognises free speech’s importance, especially political and social commentary, but draws a line at speech that overtly targets communities and risks public disorder. While some civil society voices have urged that any subjective notion of “offence” be discarded, courts consistently demand objective evidence of likely harm. For example, in Patricia Mukhim (2021), the Supreme Court held that expressing disapproval of government inaction cannot be treated as promoting hatred among communities. Likewise, in Indian Express v. Union of India (1986) the Court read freedom of the press into Article 19(1)(a), but acknowledged that the press enjoys no greater protection than the individual citizen.

Comparative Perspectives: US and EU

Globally, democracies take different approaches. In the United States, the First Amendment offers near-absolute protection for speech. U.S. courts require a very high threshold (imminent lawless action) before forbidding hateful or false speech. The Supreme Court consistently strikes down any content-based restriction unless it meets “strict scrutiny” – a compelling state interest and narrow tailoring. Thus, American law would generally protect offensive political or religious criticism, even if hurtful, unless it directly calls for immediate violence.

By contrast, the European Union enshrines human dignity and bans hate speech as a fundamental value. The 2008 EU Framework Decision obliges member states to criminalise public incitement to violence or hatred based on race, religion, or national origin. Recent EU policy further aims to classify certain hate crimes and speech as EU-wide offences and to work with tech platforms to curb online hate. The U.S. is an outlier here; most mature democracies (EU, India, Canada, etc.) consider certain hate-speech restrictions compatible with free-expression norms. India’s model aligns more with Europe: it treats communal harmony and minority dignity as constitutional goods that justify restricting some speech.

Data and Trends in India

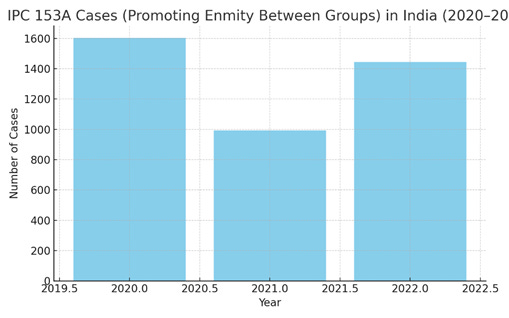

Statistical data confirm a sharp rise in hate-speech incidents and prosecutions. NCRB crime statistics (IPC 153A) show more than 1,500 cases in 2022 – a 31.25% jump from 2021. (By contrast, the 2020 figure was even higher, so 2022’s tally still trailed 2020’s peak.) In 2021, there were only 993 reported 153A offences nationwide, rising to 1,444 in 2022. The states registering the most offences were Uttar Pradesh (217 in 2022), Rajasthan (191), Maharashtra (178), Tamil Nadu (146), Telangana (119) and Andhra Pradesh (109). The marked increase in 2021–22 likely reflects heightened communal tensions and greater willingness of police to book such cases. (NCRB cautions that higher crime numbers may also result from improved registration practices.)

Electoral-age politics intensify the issue. A 2023 ADR report found 107 sitting MPs and MLAs with declared hate-speech cases against them. Over 480 election candidates in the past five years admitted such cases in affidavits. Among these, the ruling BJP had the largest share (22 MPs and 20 MLAs), but opposition figures were also represented. These figures highlight how widespread hate-speech charges are among India’s politicians.

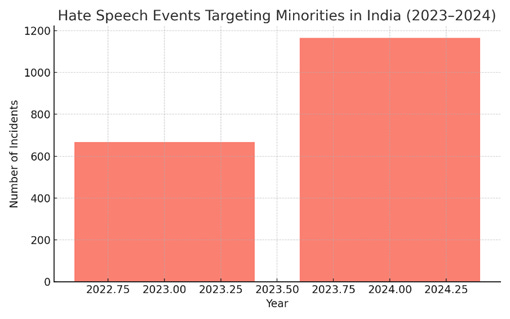

Independent monitors have documented similar trends. The India Hate Lab (CSO) reports 668 hate-speech events targeting minorities in 2023, rising to 1,165 in 2024 – a 74% spike. Many incidents clustered around election rallies and mass gatherings: nearly one-third of 2024’s incidents occurred in the intense campaign period from March to June. Notably, 80% of recorded incidents that year took place in states ruled by the BJP and its allies, underscoring a partisan dimension to communal rhetoric.

Figure 1: NCRB reports (IPC 153A) – offences promoting enmity between groups in India (2020–2022). Cases rose sharply from 993 in 2021 to over 1,500 in 2022, reflecting increased communal tensions and policing. Source: NCRB via media reports.

Figure 2: Documented hate-speech events targeting minorities in India (2023–2024). Independent watchdog data show a jump from 668 incidents in 2023 to 1,165 in the election year 2024, illustrating how political cycles have fuelled communal rhetoric. Source: India Hate Lab (CSO report).

Analysis: Striking the Balance

The core issue is balancing free discourse with the protection of vulnerable groups. The Indian judiciary’s recent pronouncements suggest a clear priority: where speech directly humiliates a group or stokes communal hate, it forfeits special constitutional protection. The rationale is practical: India has experienced horrific inter-communal violence, and unchecked inflammatory speech is seen as a credible precursor to unrest. As the Kerala High Court put it, hate speech “tendencies should be nipped in the bud” to uphold secular democracy.

Yet courts also guard against overreach. On numerous occasions, they have stressed that merely “offensive” or factually wrong statements – absent intent to disturb order – remain protected expression. Political hyperbole and religious criticism, even if acerbic, fall within the democratic dialogue unless they incite. This is why the Supreme Court in 2022 refused to convert all hateful talk into a per se crime, insisting on the need for intent or danger. Critics argue that India’s hate-speech laws are vague and liable to abuse; indeed, petitioners in Vishal Tiwari urged guidelines to prevent misuse. The Court responded that it need not define a new “hate speech” category beyond existing offences, but it sternly warned that known laws must be enforced strongly.

In practice, the balance is shifting. Increased social media scrutiny, political accountability, and judicial vigilance have put pressure on authorities to prosecute hate speech vigorously. The uptick in FIRs and convictions – and the courts’ willingness to deny bail in egregious cases – reflect this trend. At the same time, landmark rulings like Amish Devgan and Patricia Mukhim have reaffirmed core free-speech principles. Internationally, India’s approach is closer to Germany or Canada than to the U.S.: it acknowledges a qualified right to insult or offend, but criminalises words that it reasonably predicts will harm public order or minority dignity.

Conclusion

The “balancing act” in India is dynamic. Recent jurisprudence and data show a more assertive stance against hate speech: courts urge pre-emptive FIRs, stronger penalties, and contempt powers to deter communal incitement. Yet India’s constitutional promise of free speech remains alive: judges have repeatedly admonished that mere criticism or even false assertions cannot be branded criminal speech unless they meet the high threshold of incitement or violence. Ultimately, Indian law now treats hate speech not as a right at all but as a serious offence against public order. This robust approach, supported by recent data on rising incidents, aims to preserve social harmony in a diverse democracy. In doing so, India treads a middle path between the U.S. model of near-absolute speech and the stricter European hate-speech regulations, reflecting its own historical and social realities.

Sources: Indian Penal Code, s.153A, 295A, 505. Constitution of India Arts 19(1)(a), 19(2). Kedar Nath Singh v State of Bihar, (1962) Supp (2) SCR 769; Patricia Mukhim v State of Meghalaya, (2021) SCC Online SC 258; Amish Devgan v UOI, (2022) 10 SCC 1; Vishal Tiwari v UOI, (2025) 2025 Live Law (SC) 547; PC George v State of Kerala, (2025) Kerala HC (via JURIST). NCRB Crime Reports (2021–22); CSO Hate/India Hate Lab (2025 report); Times of India, PTI, India Today, Live Law, EU Comm. Reports.