Facial Recognition and the Right to Privacy: Legal and Ethical Concerns in India

An Indian Legal Perspective on Biometric Surveillance and Data Protection

Abstract

Focusing on India, this article addresses the legal and moral complexities of assigning responsibility for damages and injuries arising from the use of artificial intelligence (AI). It describes the existing legal landscape, including the case law and international developments, mapping India’s legal voids concerning decision-making processes influenced by AI technologies. Furthermore, this paper contends that the conventional legal principles will not suffice in managing autonomous systems, proposing instead a mixed model approach that combines elements of strict liability, product liability, and algorithmic responsibility. It also suggests specific legal changes to balance the need for innovation with the regulation of AI technology to ensure accountability while safeguarding human rights.

Introduction

The rapid adoption of Facial Recognition Technology (FRT) has cut across geographical boundaries in the past few years, making individuals question their privacy. A global interactive survey indicates that most countries have adopted FRT in some capacity. This debate is particularly critical in India, where the Supreme Court recognises an extensive right to privacy under Article 21, yet governments are implementing surveillance systems that encompass cameras, biometric IDs, and mobile scanners. As one commentator puts it, “India is attempting 24/7 surveillance in a country battling resource constraints.” India’s new privacy law, The Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 (DPDP Act), is set to regulate “digital personal data” eventually. For now, the conversations in India are parallel to global worries: What FRT applications are permissible? How should consent and intent be managed? What means can be taken to curb biased or disproportionate surveillance?

According to a global survey conducted in 2020, most countries now use facial recognition technology. China leads with FRT’s widespread application, and many Western governments, along with private entities, are adopting it as well. Even where bans do exist, such as in Belgium and Luxembourg, they are infrequent. In this regard, the government of India promotes Facial Recognition Technology for security and operational efficiency, whereas activists have warned of identity abuse and discrimination.

Facts

The growth of the surveillance infrastructure in India is staggering. The CCTV camera market, for example, was worth USD 2.13 billion in 2025 and is expected to grow to USD 6.87 billion by 2032, marking a CAGR of 18.2%. This increase indicates a greater number of Indian cities being blanketed by security cameras. One report states that Telangana (with Hyderabad as its capital) boasts more than 600,000 CCTV cameras – one of the highest concentrations in the world, many of which feed into biometric facial recognition systems. Amnesty International and collaborators labelled Hyderabad as “the most shrivelled place in the world,” claiming FRT was “deployed by the police, the election commission and others.” The Aadhaar biometric system places India ahead of other countries, as the World Bank noted in January 2023 that “India has the largest biometric platform in the world”, with over 1.3 billion residents enrolled. This creates a massive potential market for FRT.

Facial recognition technologies are now commonplace in India, especially in the banking sector and among telecom companies, which authenticate users through cameras and fingerprints. IMARC indicated that India’s facial recognition market (software, systems, services) is USD 382.5 million in 2024, with projections estimating it will soar to USD 887.3 million by 2033.

For example, one estimate suggests that India’s surveillance camera market will reach USD 3.70 billion by 2025, growing at a rate of 10.8% annually. In any case, the investment in surveillance systems in India is tremendous and fast-growing.

At the same time, the threat to privacy is increasing. Major breaches have made headlines in 2024, such as leaked Aadhaar data and the Star Health and Angel One breaches, which exposed health insurance and financial records. The average cost of a data breach in India reached ₹19.5 crore in early 2024, according to a PwC 2024 survey. Alarmingly, only 16% of consumers knew their privacy rights under the new DPDP Act. More broadly, 56% were unaware of any rights, and 69% did not know they could withdraw consent after it was given. There is a great deal of distrust among consumers: 32% did not believe companies take consent seriously. Organisations are aware of this as well, and 80% expect compliance challenges with the DPDP Act, and nearly half have not started implementing its requirements. The combination of low public awareness alongside extensive surveillance infrastructure creates a potential conflict between state powers and individual privacy.

Studies conducted all over the world have also shown that facial recognition frequently misidentifies women and people of colour. According to a survey based on camera deployments worldwide, FRT "frequently fails to accurately identify darker-skinned persons and women." These accuracy problems are particularly concerning in India, where lighting and camera angles can differ greatly. In fact, both accuracy and privacy issues were raised in the first FRT lawsuit in India, which was filed in Telangana in early 2022. In his petition to the Hyderabad police, activist S.Q. Masood denounced the use of FRT as "unconstitutional and illegal," claiming that it was "unnecessary, disproportionate, and lacks safeguards." As he described what happened, police had arrested him and taken his picture without giving a reason, which made him wonder: Why was my face scanned? What will happen to the data? Who can access it? These concerns match broader findings, large majorities of people (often over 75%) dislike being facially scanned by authorities. Thus, the facts are clear: Indian governments are rapidly deploying FRT (especially in urban centres), while legal protections and public understanding lag.

Issue

The main legal question is whether these facial surveillance programs violate India's constitutionally protected right to privacy and, if so, what regulations should be put in place to control them. Sub-issues include: Data security (how is sensitive biometric data protected from misuse?); Proportionality (must FRT use be narrowly tailored and necessary?); Consent (do citizens have a right to consent or opt out?); Bias and non-discrimination (how to prevent the harms of inaccurate or racially skewed FRT algorithms?); and Transparency and accountability (must authorities disclose how faces are processed?).

Legally speaking, the matter is divided into two sections: (a) Analysis of the Constitution: According to the Supreme Court, does involuntary facial recognition violate the fundamental right to privacy guaranteed by Article 21 of the Constitution? (b) Statutory regulation: What protections and limits does Indian law place on collecting and processing biometric/face data? A related policy issue is whether any regulatory gaps should be filled (for example, by detailed guidelines, legislation, or judicial oversight) to address ethical concerns.

The ethical dilemma is how to weigh the advantages of FRT (efficiency, crime control) against the disadvantages (overreach of surveillance, suppression of dissent, false suspicion of minorities). This tension is particularly high in India. Critics counter that there is no concrete proof that FRT significantly lowers crime and that it instead tracks thousands of law-abiding citizens. Law enforcement claims that FRT aids in the capture of criminals and the recovery of missing persons. Classic privacy questions are brought up by this: Should the government be able to see and identify every person in public without their consent? If not, what specific precautions are required?

Law

Right to Privacy (Article 21): The Supreme Court unanimously ruled in Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) v. Union of India (2017) that informational privacy is protected under Article 21 as a fundamental right. The Court famously declared that control over personal data, including facial images, is part of "informational privacy." Any state action that violates someone's privacy must pass the proportionality, legality, and legitimate purpose tests. Therefore, if police use facial scans, for instance, the law must expressly permit it, it must serve a compelling state interest (such as criminal law enforcement or national security), and it must only minimally violate privacy rights. The Court in Puttaswamy endorsed the concept of a “compelling state interest” and a strict proportionality analysis for biometric IDs, reflecting deep scepticism about unchecked surveillance.

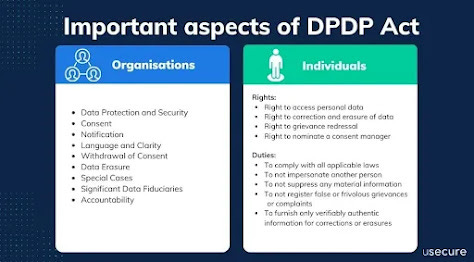

India's first comprehensive privacy law, the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023, was just passed but has not gone into effect as of mid-2025. Once it is in effect, it will control the "processing of digital personal data," which includes digitally stored biometrics and photos. With rare exceptions, consent and purpose notice are necessary for data processing. In contrast to previous bills, the DPDP Act provides baseline protection for all personal data and does not distinguish between "sensitive" and non-sensitive data. Notably, it exempts specific state uses, such as processing for public order, security, sovereignty, etc., through notification. This means that if they can justify it as security or crime prevention, government agencies (like the police) may argue that DPDP does not apply to FRT. The Act also envisages a Data Protection Board to handle complaints and impose penalties, and it enshrines modern rights (data access, correction, erasure) once it becomes effective. However, until enforcement rules and the Board are set up, DPDP’s actual impact on law enforcement practices remains uncertain.

The SPDI Rules and the Information Technology Act of 2000: India's primary privacy protections were limited before DPDP. Biometric data is included in the category of "sensitive personal data or information (SPDI)," which was established by the IT Act (as amended) and its 2011 regulations. SPDI processing entities, such as private businesses that gather fingerprints, are required to obtain consent and use "reasonable security practices." A limited criminal penalty for wrongful disclosure (Section 72A) and civil liability (Section 43A) may result from a breach of fiduciary duty. These regulations, however, have not been widely enforced in the context of surveillance and primarily apply to private actors. They do not specifically limit how the government uses FRT.

Other frameworks: India has other relevant laws and guidelines. The Aadhaar Act (2016) permits biometric-based identity (iris/fingerprints) for welfare benefits, but bars the government from disclosing data except in limited ways. (It does not directly regulate FRT by police.) Some state governments have considered their own policies: for example, Kerala passed a state-level privacy bill, and local bodies have “privacy policies” for municipal data. At present, however, there is no dedicated Indian law on facial recognition itself; use of FRT by authorities falls between general privacy norms and sectoral rules.

Global and comparative law: For context, the EU has moved to restrict FRT: the EU’s AI Act (2024) bans the creation of facial databases without consent and prohibits law enforcement use of FRT in public spaces except for major crimes and emergencies. A few countries (Belgium, Luxembourg) ban all governmental FRT outright. In contrast, India has so far not banned FR but is in the process of legislating data protection.

Analysis

Facial recognition inherently implicates privacy because it links a person’s biometric data (their image) to identity, location, and other personal details. Under Puttaswamy, any capture and use of a person’s face by the state must satisfy the privacy test: a lawful basis, a legitimate aim, and proportionality. At present, India’s laws do not explicitly authorise random FRT use in public. If police set up a “live facial recognition” scanner (for example, on CCTV or a mobile app) to scan crowds, this intrudes upon an individual’s informational privacy. The state’s interest (crime control, public safety) is important, but courts will ask: Is this narrowly tailored? Could the same objective be achieved with less intrusion? For example, if FRT is used only to search for a specific fugitive, that is more justifiable than indiscriminate scanning of all citizens’ faces.

The DPDP Act’s consent regime sheds light on the expected standards: normally, processing requires free and informed consent. But the Act’s own exemptions swallow that rule in important cases: any use by “instrumentalities of the State” notified under national security or public order is exempt. Thus, unless the government voluntarily makes its FRT programs subject to DPDP principles, there is no automatic requirement for consent or notice when police scan faces. In practice, this means a citizen’s photo taken by police may not trigger DPDP claims of unlawful processing, because law enforcement could claim an exemption. This leaves room for broad surveillance. The lack of an explicit statutory hook is a legal loophole: neither the Constitution nor DPDP gives clear “permission” for specific FR deployments, but neither flatly forbids them either. This ambiguity is why litigants like Masood have challenged such programs as illegal.

The rules of proportionality demand careful limits. For instance, King Stubb & Kasiva note that both consent and purpose limitation are core to biometric data use. FRT must be for a “legitimate purpose critical to the Data Fiduciary’s function,” and data collected should be discarded when that purpose ends. Under DPDP, if consent is the basis for processing, a citizen should be able to withdraw consent. However, police data collection is rarely labelled “consensual;” it is typically asserted as duty-bound. Still, ethical norms suggest that even the police should define clear purpose-limits (e.g. identifying specific suspects) and avoid keeping biographic data longer than needed.

Crucially, the use of FRT by authorities can easily overshoot. If cameras scan the faces of bystanders, or if banks/government link identities to crowds, the natural “expectation of privacy” in public spaces diminishes. Yet even in public, anonymity has value in a free society. The Supreme Court has hinted that anonymity is part of free speech and dissent. The Puttaswamy judgment warned that “every citizen has a right to go about in public spaces without intimate surveillance.” When FRT is integrated into CCTVs, that warning takes on new force. Technology now makes it feasible to identify anyone on public streets at any moment. This potential for mass identification was not imagined when Article 21 was drafted, but courts may well hold that relentless face-scanning chills privacy.

Ethical issues: The known biases of FRT compound the legal problems. Studies (and common experience) show FRT is less accurate for women and darker-skinned individuals. In India’s diverse society, errors disproportionately affecting minorities (low-caste Dalits, indigenous Adivasis, or Muslims) are especially worrisome. The Telangana lawsuit emphasises this: its petitioner, a Muslim activist, feared misidentification and harassment. These concerns are backed by data: biometric algorithms trained on lighter-skinned datasets frequently misfire in India. The lack of a data protection law was noted in the same breath as this bias problem. Without strict auditing or legal remedy, a person wrongly “flagged” by FRT might face detention or police scrutiny with no quick way to contest it.

Another ethical problem is consent and transparency. When banks or companies install FRT (for entry or login), they usually ask for consent. But when the state uses FRT, there is no opt-in mechanism. Many Indians have never been informed that their faces might be used in state databases. As one digital rights lawyer noted, “most people are not even aware they are being shrivelled” by these systems. This lack of transparency violates best practices. The DPDP Act’s notice-and-consent regime was designed precisely to give individuals a choice. If FRT programs remain opaque, they circumvent that protective intent.

Globally, the trend is to require warrants or judicial oversight for intrusive tech. India currently has no law requiring a court order for an FRT search. If a citizen protests during a random face-scan (like Mr. Masood did), police typically have no obligation to justify their action. This runs counter to jurisprudence, which generally imposes at least some checks on police powers. In practice, then, the legal position is unsettled: rights exist on paper, but enforcement may lag.

Conclusion

Facial recognition technology offers powerful tools for identification and security, but in India, it poses serious privacy and ethical challenges. The Supreme Court’s decision in Puttaswamy makes clear that Indians have a fundamental right to informational privacy, and any surveillance regime must be lawful, necessary, and proportionate. The new DPDP Act, once fully in force, will introduce consent and data-protection principles even for biometric processing. However, its many exemptions for government activity leave uncertainty. Notably, the Act has not yet come into effect, meaning today’s facial recognition initiatives proceed under the old regime.

On the facts, India is rapidly deploying FRT without clear rules. Millions of faces are being scanned even as only a fraction of people understand their rights. The risk of abuse is real: biased technology could wrongly mark innocent people, and unchecked surveillance could chill freedoms. As a result, activist groups and even individuals (like the Telangana petitioner) are pushing for court intervention and legal clarity. India’s government and courts should heed these concerns. Legally, they may consider requiring procedural safeguards: for instance, limiting FRT to defined crimes, mandating advance notice, or ensuring mechanisms to contest misidentification. Ethically, transparency and accountability must improve – the public should know when and why their faces are being scanned, and data should not be retained longer than necessary.

In sum, facial recognition brings India to the frontier of privacy law. As the technology spreads, Indian policymakers and judges will have to reconcile its benefits with constitutional rights. The global examples (from EU restrictions to outright bans) offer models for caution. In India, a balance must be struck: preserving legitimate law enforcement capabilities while upholding the individual’s dignity and privacy. Achieving that balance will require robust legal standards (likely rooted in DPDP and Article 21 jurisprudence) and public oversight. Only then can India deploy facial recognition “the right way” – if at all – without eroding the privacy rights that its courts have vowed to protect.

Sources:

Indian Supreme Court case law (K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India, 2017); Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023; IT Act 2000 (SPDI rules); news and analysis on Indian FRT and privacy.