Digital Illusions: Why Your Insta-DMs Aren’t as Private as You Think

Teenagers, Influencers, Data Leaks, and Your Digital Footprint

Abstract

Instagram’s direct-messaging (DM) platform has emerged as a principal channel of communication for India’s youth, yet it occupies a legal purgatory in which users’ expectations of confidentiality confront the data-collection imperatives of profit-oriented technology companies. This article examines how, despite the illusion of privacy displayed during DMs in Instagram, they are unencrypted, subject themselves to intelligence of Meta and expose users, more specifically those underage, to scrutiny and data leakage along with profiling. Despite the legal system of India evolving as per the requirements, there is still not enough protection. Although privacy has been made a fundamental right by Supreme Court in Puttaswamy case, 2017, the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 has significant shortcomings regarding enforcement, consent policy, and child-contracting policy. Having analysed how metadata are exploited, the susceptibility of adolescent users to the given vulnerability, and the comparison between the Indian regulatory environment and the GDPR in the European Union, the paper argues that the DM feature of Instagram is a convection of a privacy illusion. The lack of encryption, elasticity of consent policies, as well as the ineffectiveness of the redress mechanisms perpetuates a default culture of surveillance in the digital world. The article thus suggests following real-time legal changes such as mandatory end-to-end encryption, the use of a solid architecture of consent, increasing the age of digital consent, creating a data-harms tribunal, and launching a data-privacy awareness campaign, in order that privacy can find its way out of theory to become a right that can operate in practice.

Introduction

To understand how digital privacy is compromised, we must first look at the platform that millions trust for confidential communication. Instagram has evolved to be a multilateral digital environment, where users not only share photos but also send direct instant messages, enjoy video conference, and broadcast messages that have a specific lifespan through direct messaging. To a significant number of users aged 15-25 the direct messages serve as the online analogue to the individual room. They exist in a legal grey zone, where user privacy expectations clash with corporate monetisation.

This ambiguity is not merely hypothetical. In 2021, the Facebook whistle-blower revealed that messages on Instagram and Messenger were generally available to automations at Meta to profile and target its users. The matter is even bigger in India where the internet access is growing at a dramatic pace, and privacy laws in India remain underdeveloped.

The current article strives to narrow the gap between what the users consider as privacy and what is legally secure as per the enforceable law. Using Instagram as a case study, it poses questions of relevance to more general concepts of surveillance, consent, adolescent exposure, and the insufficiency of the status quo of the current surveillance environment in India. This illusion of control becomes even more concerning when we examine how the platform actually functions and how users interact with it.

From Feed to Footprint: The Factual Matrix

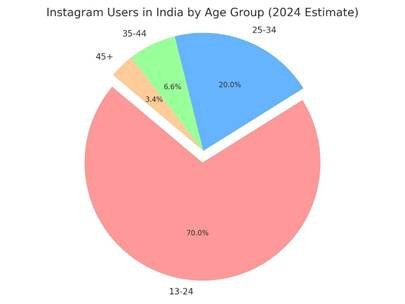

As of today, there ever more than 229 million Instagram users in India and people aged 13-24 take up over 70 percent of the said population. The direct-messaging feature of the platform is not encrypted, and by default, the company can review it using its algorithms.

Figure 1: Instagram Users in India by Age Group (2024 Estimate).

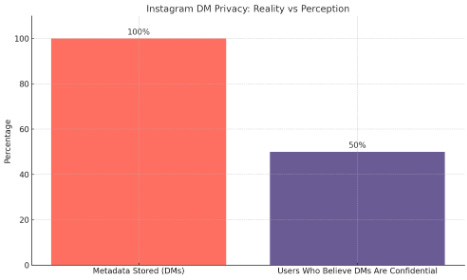

Mozilla Foundation report published in 2022 showed Instagram would store metadata of the DMs, such as whom the users talk to, at what times, and how many times even after the messages get deleted. At the same time, a Consumer Reports study found out it was more than 50 percent of Instagrammers who mistakenly believed that their DMs were completely confidential and safe against external access.

Multiple data breaches have also transpired. There have been some high-profile cases of DMs being leaked in the course of a brand-partnership conflict, an extreme example was when the DM of a well-known Indian influencer was leaked, and people engaged in numerous online attacks against the person. The platform blamed it on user error, and no one was criminally or civilly responsible.

Figure 2: Instagram DM Privacy: Reality vs Perception.

This raises a critical question: if even celebrities lack protection, what safeguards exist for ordinary users whose privacy rights remain undefined in practice? These real-world breaches highlight the legal vacuum users fall into. This brings us to the central legal questions raised by Instagram’s data practices.

Legal Issues: The Myth of Consent and the Right to Privacy

The key legal questions arising in this digital landscape are:

1. Is user consent valid when conditions and methods of data processing are hidden in the complex terms of use.

2. Enquiry into the extent to which the government of India via statutes, gives sufficient protection to the personal chat and related metadata shared in the social media.

3. What will be done with leaks or misappropriation of such data and how that individual affected can be repaid.

4. Whether minors, who are an important part of Instagram users, face weakness due to gaps in the currently existing legal safeguards.

These questions are not only essential to jurists, but also, to all the individuals who chat online without credentials of privacy. To answer these questions, we must explore both constitutional guarantees and the statutory protections offered under Indian and international law.

Law: Constitutional and Statutory Framework

1. Constitutional Right to Privacy

The Supreme Court judgment in Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) v. Union of India [(2017) 10 SCC 1] established privacy as a fundamental right guaranteed by Article 21. However, this protection was qualified by the fact that the Court allows carrying out reasonable limitations when there are state or commercial interests involved.

2. The Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 (DPDP Act)

The first in-depth data protection law in India is quite extensive, but it contains several interesting gaps:

• It permits “deemed consent” in numerous circumstances.

• It does not include non-personal metadata, data about contacts and the time when communications happened.

• It does not place a greater burden on protection of children who are 13 or above years old- a weakness that is not in line with global recommendations.

• Its enforcement role is lacking because a centralised Data Protection Board is not very independent.

3. Information Technology Act, 2000 (Amended)

There are section 66C and 66E which applies sanctions to identity theft and the invasion of privacy, but these are not much applied on social media related matters due to unresolved questions of jurisdiction and evidence.

4. International Benchmarks: GDPR (EU)

In contrast, the GDPR explicitly mandates clear consent, user control over data, and penalises even metadata misuse. It treats teenage users (below 16) as a protected category, unlike India’s DPDP Act.

Analysis: Instagram DMs, Data Politics & Youth Vulnerability

Instagram’s data-consent framework is flawed. In order to open an account, the user is forced to agree to long, legally cryptic conditions which function as take-it-or-leave-it terms, offering users no meaningful choice. This type of arrangement contradicts well-known jurisprudence and GDPR-accepted principles of free, informed, and specific consent. Having established the gaps in the legal framework, we now turn to their real-life impact, especially on teenagers, influencers, and everyday users.

1. Metadata Surveillance: The timestamp of received and sent messages as well as their recipient and device IDs are kept and examined, even without reading them. Such metadata often reveals more about a person’s social network than the message content itself. Currently, the Indian law system lacks enforcement in terms of regulating metadata gathering by a non-governmental organization. This broken consent model leads us to a deeper issue, metadata surveillance, where even deleted messages leave a trace.

2. Teenage Users: Immature risks and minimal protection lead teenagers for routinely profiled for ad targeting, yet most have little understood of the privacy trade-offs involved. The Data Protection Development Policy Act (DPDP) sets 13 as the age of consent for data processing; however, empirical research indicates that even 17-year-olds do not possess full cognitive maturity to grasp the trade-offs involved. GDPR requires parental consent until 16 and thus provides extra-protective criterion. The risks are further compounded when the platform’s most vulnerable users, teenagers, are exposed to profiling they can barely understand.

3. Data Leaks and No Solutions: When DMs spill, users often find no legal redress that they can identify. Section 66E requires making a criminal complaint that proves painful in terms of time consumption and futile due to the complexity of jurisdiction. Damages under the tort law are costly measures used as civil remedies and not very much have been utilised in India. But the most visible harm emerges during data leaks, events that strip users of control and offer them little to no recourse.

Taken together, these factors paint a bleak picture of DM privacy in India. A fundamental rights framework exists, but its enforcement remains cosmetic.

Conclusion

Insta-DMs form part of a privacy illusion and it reveals the failure of the Indian law to address such illusion in a meaningful manner. Since Puttaswamy had formulated the privacy as a fundamental right, the DPDP Act has still a long way to go in bringing the right into effective application at user-levels like social-media messaging. The exploitation of this gap in the regulations thus falls at the expense of teenage users and influencers, who then facilitate a surveillance-by-default digital culture.

Recommendations

1. Mandate End-to-End Encryption for All DMs by Law. Enforce it as a Statutory obligation under IT Act/OR the DPDP Rules.

2. Revise Consent Architecture: All apps have to offer easy layered disclosures of what they are collecting and why.

3. Raise the Age of Digital Consent to 16: Legalize India so as to better safeguard teens so in line with GDPR standards.

4. Create a Fast-Track Tribunal for Data Harms: In a span of less than 30 days, privacy grievance ought to be dealt with by a special bench under the Data Protection Board.

5. Launch a Public Awareness Campaign to make the youth aware of digital footprint, especially in regional languages.

Unless such reforms take place, privacy on Instagram will remain an illusion, visibly offered, but legally empty.

Sources

Justice K S Puttaswamy (Retd) v Union of India (2017) 10 SCC 1

Digital Personal Data Protection Act 2023 (India)

Information Technology Act 2000 (India)

General Data Protection Regulation 2016 (EU)

Mozilla Foundation, 'Privacy Not Included Report' (2022)

Consumer Reports, 'Social Media Privacy Audit' (2023)